Important information

This article features documents that contain racist and abusive language. Original language is preserved here to accurately represent our records and to help us fully understand the past.

Nine protestors

In 1971 nine black men and women were put on trial at the Old Bailey for causing a riot at a protest march. Their names were Darcus Howe, Frank Crichlow, Rhodan Gordan, Althea Jones-Lacointe, Barbara Beese, Godfrey Miller, Rupert Glasgow Boyce, Anthony Carlisle Innis and Rothwell Kentish. These men and women became known nationally as the ‘Mangrove Nine’. When all nine defendants were acquitted of the most serious charges after a long 55-day trial, it was widely recognised as a moment of victory for black protest.

At The National Archives we hold a series of letters, photographs and police statements relating to the trial of the Mangrove Nine and the history of Britain’s Black Power movement.

A sanctuary at the heart of a community

In post-war Britain, black British people faced widespread racial discrimination and unfair treatment in their daily lives. Some white people refused to rent properties to non-white tenants. Black people were also sometimes refused service in restaurants and shops. Like many immigrant groups, Trinidadian migrants in the working-class neighbourhood of Notting Hill, London, established restaurants, churches, clubs and shops that reflected their culture and provided a safe space for community-building.

The Mangrove Restaurant was an important example of this, serving Trinidadian food to first generation migrants and their children. As the Trinidadian migrant Clive Phillip put it, ‘It was like a sanctuary. It was family, a base for support.’

The Mangrove was a hub for Notting Hill’s black community, but it was also a meeting space for community organisers, activists and intellectuals in the area.

Inside, the restaurant reflected the new cosmopolitan culture of 1970s Britain: with a photograph of Beatles star John Lennon hanging on the wall alongside a mural of mangrove trees, African figurines and posters decrying police brutality. Black intellectuals like CLR James and Lionel Morrison and celebrities like Jimi Hendrix, Bob Marley, Diana Ross, Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone, Sammy Davis Jr and Vanessa Redgrave had all been seen there.

Persecution of the Mangrove

Between January 1969 and July 1970, the police raided the Mangrove Restaurant 12 times. No evidence of illegal activity was found. The raids on the Mangrove were seen as reflecting a wider culture of oppression.

On 9 August 1970, a group of Black Power activists led 150 people on a march against police harassment of the black community in Notting Hill. They called for the ‘end of the persecution of the Mangrove Restaurant’. During the march, violence broke out between the police and protestors.

A public statement

The Action Group provided a public statement to explain the reasons for the protest march against police harassment and the persecution of the Mangrove Restaurant. This group was set up by anti-racist activists, like the leader of Britain’s Black Panthers Althea Jones-Lacointe, and local community leaders.

We, the Black People of London have called this demonstration in protest against constant police harassment which is being carried out against us, and which is condoned by the legal system.

In particular, we are calling for an end to the persecution of the Mangrove Restaurant of 8 All Saints Road, W.11, a Restaurant that serves the Black Community.These deliberate raids, harassments and provocations have been reported to the Home Office on many occasions. So too has the mounting list of grievances such as raids on West Indian parties, Wedding Receptions, and other places were Black People lawfully gather.

We feel this protest is necessary as all other methods have failed to bring about any change in the manner the police have chosen to deal with Black People.

We shall continue to protest until Black People are treated with justice by the Police and the Law Courts.

Action Group for the Defence of the Mangrove.

Copies have been sent to:

Home Office,

Prime Minister,

Leader of the Opposition,

High Commissioners of Jamaica, Trinidad, Guyana and BarbadosStatement by the Action Group. Catalogue reference: HO 325/143

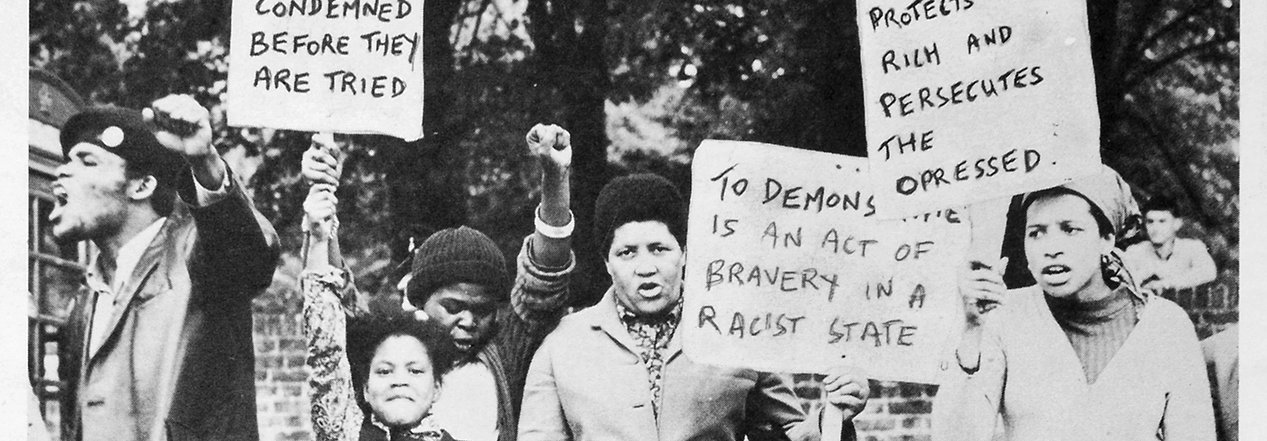

The protest march

Colin Lynch, Detective Constable attached to Special Branch, New Scotland Yard, was directed by his senior officer to ‘attend a demonstration organised by coloured people to protest against alleged police oppression in the Notting Hill area.’

He explained further: ‘I was told that in view of the violent sentiments expressed in some of the literature publicising the demonstration it was feared that public disorder might occur.

'Accordingly I was instructed to take photographs of the demonstration to provide a sequential record of events should disorder ensue.’

A peaceful group of protestors were followed by many police officers. Catalogue reference: MEPO 31/21.

A number of photographs from police and journalists are held by The National Archives. Catalogue reference: MEPO 31/21.

Protesters were physically restrained by police officers (catalogue reference: MEPO 31/21)

The trial of the Mangrove Nine

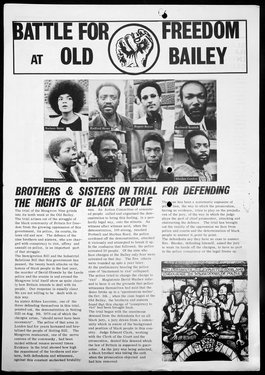

The demonstration and the eventual three-month trial of the Mangrove Nine received national attention in the press and among politicians and activist groups.

The defendants used the courtroom and the media attention of the trial as a platform to critique the racism of the police, the justice system and the British state.

A pamphlet printed in defence of the Mangrove Nine. Catalogue reference: HO 325/143.

In his summing up at the end of the trial, the presiding judge, His Honour Judge Edward Clarke QC, famously noted that the trial had ‘regrettably shown evidence of racial hatred on both sides’.

Metropolitan Police attempted, unsuccessfully, to have this statement withdrawn. While it was not until the 2000 Equalities Act that the police would come under anti-discrimination law in Britain, the trial was historic in including the first judicial acknowledgement of racial prejudice in the Metropolitan Police.

Thanks in part to the Mangrove Nine trial, the 1976 Race Relations Act attracted broad support. This law expanded the scope and power of anti-discrimination law in Britain and was the foundation of today’s Equality and Human Rights Commission.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- MEPO 31/21

- Title

- Metropolitan police file on Black Power demonstrations featuring original statements, newspaper cuttings and photographs

- Date

- 1970–1973

-

- From our collection

- HO 325/143

- Title

- Home office file on the Black Power movement and the relationship between police and immigrants

- Date

- 1970–1972