The papers of Nuestra Señora de Covadonga, a Spanish treasure galleon

mage caption

Letters sent aboard the Covadonga (left) and ship’s papers (right), 1742–3. Catalogue reference: HCA 32/135/8

This previously unknown set of records from an 18th-century galleon shines a light on one of history's most significant trade routes. It was found among roughly 500,000 papers taken from ships in the Prize Papers collection, which are being digitised in collaboration with University of Oldenburg.

Bridging the Pacific

From 1565 to 1815, enormous and well-armed Spanish ships, known as galleons, sailed across the Pacific Ocean each year, traveling back and forth between Acapulco in Mexico and Manila in the Philippines.

On their westward leg, these ships carried vast cargoes of silver coins (mostly denominated as pesos or pieces of eight), along with small amounts of other goods, which allowed them to buy a range of merchandise in Manila, from Chinese jade and silk, to Sumatran spices and Japanese lacquered furniture. These were some of the most valuable commodities in the world and, when transported back to Acapulco, merchants flocked from as far away as Peru to buy them at annual fairs.

Traders then either sold these goods in the Americas or exported them across the Atlantic to Spain and to other European markets, making the Manila galleon trade route one of the most significant in global history. It linked Asia to Central America and, indirectly, to Europe, with the goods exchanged shaping the fashions, languages and cuisines of three continents for 250 years.

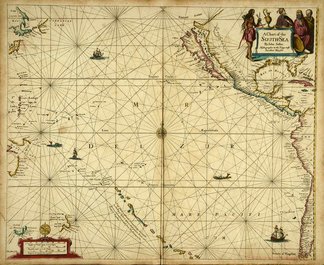

A map of the Pacific by John Seller that depicts galleons, Atlantic Maritimus, around 1698. Catalogue reference: FO 925/4111 fo.36

Yet this trade came with a high human cost. Most of the silver transported on these galleons came from two places, a huge mine at Potosí in Peru and smaller but still significant operation at Zacatecas in Mexico. Some estimates claim that mines in the Spanish Americas accounted for as much as 80% of the silver mined globally by the 18th century. The workers that toiled in these mines were largely indigenous or of African descent and most worked under regimes of forced labour, compelled to meet annual quotas of silver. Precious metals were extracted at the cost of thousands of lives, making the Spanish crown rich and powerful, while also supercharging the economy of China, which ultimately received a high proportion of the silver mined via trade.

The capture of Nuestra Señora de Covadonga

Nuestra Señora de Covadonga was one of the galleons that sailed this Pacific route from 1731. At 1,000 tons with 50 cannons installed over three decks, the Covadonga was a formidable warship capable of transporting cargo but also defending itself against all but the most powerful naval vessels. For 12 years, it passed back and forth between Acapulco and Manila with minimal incidents, but its 1743 voyage was to be a disaster.

The Covadonga sailed from Acapulco on 15 April 1743, weighed down by silver worth roughly £60 million today, and 530 people, half of them crew and the remainder passengers. To make room for this volume of people and silver, the newly-appointed Commander, Geronimo Montero, had ordered the removal of all but 13 of the 50 cannons, leaving the ship far below its full strength. This was ill-advised as Spain was at this time embroiled in a conflict against Great Britain known as the War of Jenkin’s Ear (1739–48).

While the galleon made its way across the Pacific safely, on 30 June, when off Samar in the Philippines, its crew spied a sail in the distance. When the approaching vessel hoisted a British flag, the Covadonga’s crew readied themselves to fight.

The approaching ship was commanded by Commodore George Anson, who in 1740 was charged with leading a fleet of six warships into the Pacific by the British Admiralty, to raid vulnerable Spanish cities and to capture the Covadonga. Treasure galleons were always tempting targets for Spain’s European rivals, who planned to intercept them each time that war broke out in the hope of disrupting the Spanish Empire’s economy. Anson’s voyage was poorly planned, however. His ships were overcrowded and he lost most of his crew through storms, mutiny and disease before really entering the Pacific, while the soldiers he was allocated came from Chelsea Hospital, all being either too old or infirm for regular service.

George Anson, 1st Baron Anson, after Sir Joshua Reynolds. Oil on canvas, 1755–1810, based on a work of 1755. NPG 518 © National Portrait Gallery, London

By the time that Anson attacked the Covadonga, after months of waiting in ambush in the Philippines, he had but a single vessel remaining, the Centurion. It would not be an easy battle. The two warships clashed and after around 90 minutes of close quarters fighting, Montero surrendered. By overloading his ship he had left it exposed and indefensible.

Anson’s ragged crew took the captured Covadonga into Canton, China, where the ship was sold, and the silver unevenly distributed amongst the crew – a cause of protracted lawsuits when they eventually returned to England on 15 June 1744.

The Covadonga’s papers at The National Archives

Before Anson could securely claim his plundered silver, he had to prove that his capture was legal before the High Court of Admiralty in London. The Court’s prize jurisdiction heard the case and roughly 100 documents taken from the Covadonga, including the ship’s administrative papers and letters intended for delivery to Manila, served as exhibits.

These legal proceedings are the reason that the Covadonga’s papers survive at The National Archives as part of the Prize Papers (HCA 32), along with similar materials taken from roughly 35,000 ships between 1652 and 1815. Together, the galleon’s papers reveal much about the voyage of the Covadonga, its crew and passengers, but also the many people whose lives were connected through the Manila galleons.

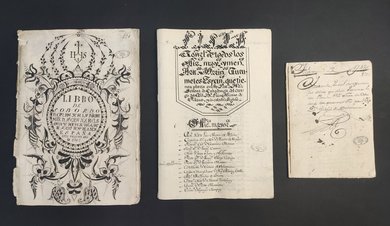

Figure 1. Three volumes of the Covadonga’s ship’s papers. Catalogue reference: HCA 32/135/8, B 2, B 4 and B 5

These three volumes (figure 1) are some of the Covadonga’s ship’s papers. The beautifully illustrated example on the left is the vessel’s register, which recorded the merchants and colonial officials who had silver aboard in great detail.

In the centre is the ship’s muster book for a previous voyage that listed the Covadonga’s crew and passengers. It notes that, remarkably, the crew included 128 children, making up around half of the sailors aboard. There were also 18 criminals chained below deck on the ship, who were being shipped to work on the King of Spain’s galleys.

On the right is a small book in which an officer noted each occasion that the Covadonga fired its cannons in salute and, as this was a Catholic vessel, it notes that they fired their cannons to celebrate a number of saints’ days.

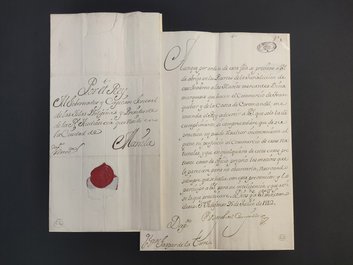

Figure 2. Dispatch sent aboard the Covadonga, a duplicate of a letter to Governor Gaspar de la Torre y Ayala. Catalogue reference: HCA 32/135/8, C 2

Many official dispatches were also aboard the Covadonga, such as a letter (figure 2) sent to the Spanish Governor of the Philippines, Gaspar de la Torre y Ayala. It was sent by Raphael Campillo from the Royal Palace of San Ildefonso, located 80 km north of Madrid and shipped first to Veracruz in Mexico before then being transported overland to Acapulco for onward delivery to the Philippines. The letter gives de la Torre a simple order: to allow Danish traders to operate at Tranquebar (Tharangambadi) in southern India. While this seems like a distant region to concern a governor of the Philippines, it did because the Spanish crown used the islands as more than a trade outpost. The site was also used to project power across the Indian Ocean. Criss-crossed by highly complex political and commercial networks, it was a maritime region most European merchants could only dream of trading in.

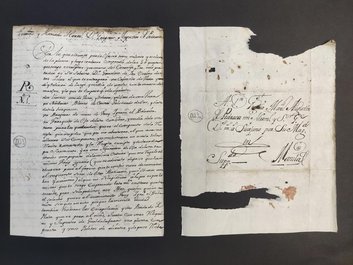

Figure 3. Mercantile and personal letters aboard the Covadonga. Catalogue reference: HCA 32/135/8, D 23 and D 23a

A final set of documents taken from the Covadonga include mercantile and personal letters (figure 3). The letter (left) with its roughly opened envelope (right), was sent by Joseph Elias Pedraza at Acapulco to his brother Gregorio in Manila. It details the many gifts he sent to Gregorio on the galleon, which included a 'white beaver [fur] hat trimmed with gold and [ornamented with] a tortoiseshell ribbon', along with holy relics from Guadalajara and newly painted portraits of the two brothers.

The letter also goes into recent deaths in the family in some detail, which was a common subject for personal letters in this period. Sadly, because the Covadonga was captured by Anson, Gregorio received neither this letter nor the gifts that Joseph sent to him.

This bundle of papers, taken from the Covadonga and transported all the way back to England by Anson’s crew, show us that it was carrying more than valuable cargo. It was, for a time, a home for hundreds of people, a channel of political communication across the global Spanish Empire and a means for families to remain in contact, even when separated by the Pacific Ocean. Despite the importance of the Manila galleons their papers are not the kind of records that would normally survive. They concern few men or women of any lasting fame and relate to the transient world of seafarers, who left far fewer traces than those who spent their lives on land.

While they were never delivered, materials from the Covadonga are now available online in the Prize Papers Portal, making them freely available across the world.

Records featured in this article

-

- From our collection

- HCA 32/135/8

- Title

- Captured ship: La Nuestra Señora de Covadonga

- Date

- 1744