A documentary heritage

The National Archives holds over 120 documents which contain evidence of William Shakespeare’s life as a playwright, actor and property owner. About 40 of these are considered so significant to the study of his life that they are listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

Shakespeare has a part to play in records of civil and criminal legal cases, property transactions, tax defaults, and his association with London theatres and companies of players including their royal patronage.

Shakespeare's will

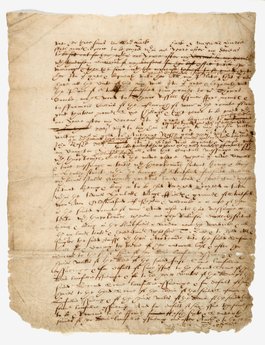

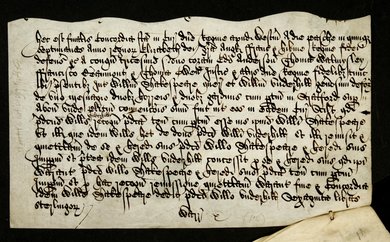

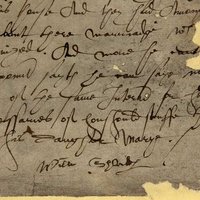

One of our most precious treasures is Shakespeare’s fragile last will and testament from 1616, which contains three of the six surviving examples of his signature.

The first page of the will. Catalogue reference: PROB 1/4.

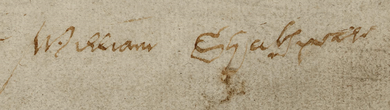

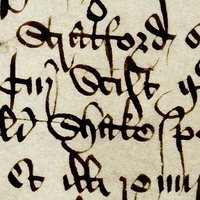

One of Shakespeare's signatures as it appears on the will

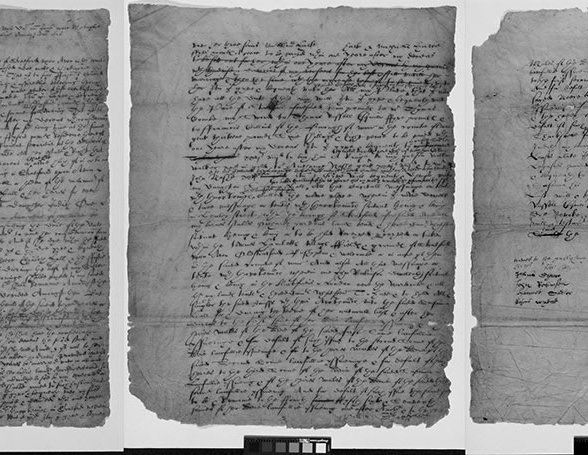

We hold Shakespeare’s original will because, after his death in 1616, it was submitted to the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in London to be proved to allow his executors to carry out his last wishes. Although it is a formal legal document, lacking in any obvious sentiment, people have puzzled over its wording for the last 250 years in an effort to understand more about the writer and his relationships with those people to whom he left bequests.

-

- From our collection

- PROB 1/4

- Title

- Shakespeare's Will

- Date

- 22 June 1616

The second best bed

Shakespeare's wife Anne is only mentioned once in the playwright's will, receiving the infamous bequest of the second-best bed:

Item I gyve unto my wiefe my second best bed with the furniture

This is often interpreted as an insult and evidence of the nature of the couple's relationship. However at that time, the first-best bed was always an heirloom left to the heir. New research is also shedding light on the financial rights of widows at this time, which may show that Anne was in fact better provided for than the will suggests.

Why did Shakespeare only leave his second-best bed to his wife?

This blog by Dr Amanda Bevan suggests a new understanding of this particularly famous bequest and provides some exciting analysis of the dating of the will.

Conserving the will

Shakespeare’s will went on display in 2016 as part of our exhibition By Me William Shakespeare. In preparation, we took a fresh look at the will from historic, scientific and conservation points of view, and carried out renewed conservation treatment.

Video Series: Conservation of Shakespeare's Will (Opens in a new tab)

The painstaking work of our Collection Care department in conserving the will is explained in this series of videos.

Shakespeare's finances

Property

Shakespeare was involved in a number of property transactions. His purchase of New Place in 1597 in his home town of Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire is well documented in the records of the Court of Common Pleas.

The record confirming the purchase is referred to as a ‘foot of fine’ because the agreement or ‘fine’ was written out three times on a single membrane of parchment and then cut into three along wavy lines. One section was given to the buyer, one to the seller, and the bottom section (foot) was retained by the court.

The foot of fine. Catalogue reference: CP 25/2/237/39ELIZIEASTER.

-

- From our collection

- CP 25/2/237/39ELIZIEASTER

- Title

- Foot of fine for New Place

- Date

- 1597

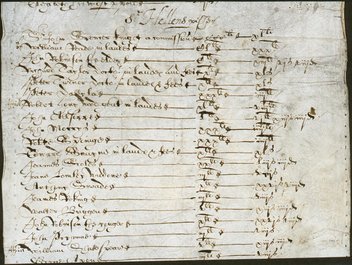

Taxes

We have five surviving documents which record Shakespeare as a taxpayer in the London parish of St Helen’s Bishopsgate, dating between 1597 and 1600 and indicating that he failed to pay amounts of 5 shillings and 13 shillings 4 pence when they were due.

Shakespeare is listed towards the bottom of this 1598 list of tax defaulters. Catalogue reference: E 179/146/369.

-

- From our collection

- E 179/146/369

- Title

- London tax commissioners listing Shakespeare among tax defaulters 1598

- Date

- 1 October 1598

Traces of Shakespeare

In addition to documents specifically about Shakespeare's financial and legal affairs, we also hold records that mention Shakespeare. These fleeting glimpses allow researchers to piece together the details of the playwright's life.

Shakespeare witnesses a legal case

One of the legal cases which provides evidence of Shakespeare’s life did not cast him as either plaintiff or defendant, but rather as a key witness. The case of Bellot v Mountjoy regarding the payment of a dowry was heard in the Court of Requests in 1612 and the court documents include 24 mentions of Shakespeare’s name and, on his deposition, the earliest known example of his signature.

Shakespeare's signature. Catalogue reference: REQ 4/1/4/1.

-

- From our collection

- REQ 4/1/4/1

- Title

- Belott v Mountjoy

- Date

- 11 May 1612

Royal Patronage

Several records refer to the appointment of Shakespeare and his associates as the King’s Men in May 1603 shortly after the accession of James I. A proviso was made that they could only perform ‘when the infection of the plague shall decrease’.

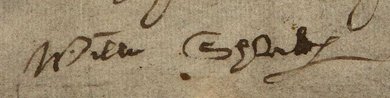

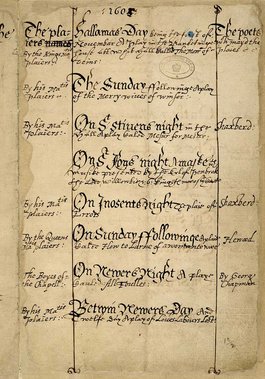

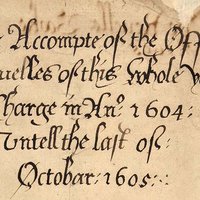

One of many variations of Shakespeare’s name is given in the accounts of the Master of the Revels in 1604-05 where he is described as ‘Shaxberd’, one of the ‘poets who which the plays’ presented before the royal court.

The name Shaxberd appears in the right hand column of these accounts. Catalogue reference: AO 3/908.

-

- From our collection

- AO 3/908

- Title

- Accounts of the Master of the Revels

- Date

- 1604 – 1668